|

|

Signalman Lawrence Fitton wrote of

his experiences in a letter:

'As you know

all things went well although jerry tried his hardest to delay us.

Then our day consisted of minesweeping and at night keeping a good

lookout for bombers laying more mines around us, but all nights

didn't pass easily and jerry found himself being forced back he

brought all sorts of foul inventions into play. Mines disguised as

buoys and motor boats pilotless and full of high explosives. This

occurred so often with night raids and E. Boat raids that the nights

became nights of terror and when day came we could sleep in peace.

This continued until it was decided to storm Le Havre by sea. So it

came about that we were detailed to sweep the entrance to the

harbour. At first we were met with heavy gunfire but, towards the

end of the week we had the upper hand and we started to get a little

bolder and go closer inshore.

Then came the

grand finale over the horizon came six allied planes and we being

close inshore it was quite natural for them to mistake us for enemy

vessels. Therefore after a few mistakes in positioning friendly

shipping they attacked. I had only just come off watch and drunken

my tot of rum, when a terrific explosion lifted us off the floor, or

as we say deck, and flung me and my pals from one side of the ship

to the other. We had been hit with a salvo of rockets from a

typhoon. In the space of a few seconds I was on my feet and running

for top deck. On reaching it I saw several of my mates, chaps like

myself who only a short time ago had been sunbathing, lying

scattered about in huddled heaps. As the order to abandon ship was

given I looked up and saw several of our own planes diving down. Too

late I dropped down and when I stood up I was surprised to find I

was covered all over in blood and having as yet felt no pain

whatsoever.

Next I found

myself in a motor boat leaving the ship. This means of transport was

apparently too good for me, for when the planes had attacked they

had riddled the motor boat, and we soon found ourselves sinking.

Still not despaired I kicked off my shoes and commenced swimming,

but I soon found myself without lifebelt and I realised it must have

been punctured anyhow. To add to his jerry started firing 9.2 heavy

calibre shells at clusters of boats and also we were in an unswept

part of the minefield, but after about 90 minutes of clinging to

wreckage and attempting to swim, because by now the salt was in my

wounds, I was eventually picked up and rushed by high speed launch

to a hospital ship, from there to England, hospital and home.

But often I

think of my pals who not so fortunate as me were either crippled or

dead. That is why I find myself in no position to grumble at being

away from home as throughout it all I managed to come up smiling and

thank God for allowing me to live when better men died.'

(Source: Michael Fitton, son, Jan

2009)

AB

Bert Hughes in BRITOMART recalls:

'I

was on watch and sitting with my back to the winch helping another

seaman to make a wire splice. Suddenly there was a tremendous

explosion and there was water everywhere. I assumed that we had struck

a mine ourselves. We knew at once they were our planes. We were told

they weren't ours, but they had the special striped D-day markings on

and you couldn't mistake a typhoon for anything else. I jumped to my

feet and everything was confusion. When we looked towards the bridge,

which had just been struck by a salvo of Typhoon rockets, it was a

terrible mess. BRITOMART started to circle and to settle quite

quickly. Eventually an order was given to abandon ship, but not from

an officer because they were all dead or dying. We all went into the

water. I will never forget the thunder of that attack. There can't be

anything like the noise and shaking of it.'

John Price, a telegraphist

on BRITOMART:

'My

first thought was "What the hell are the silly bastards playing at?",

and this was overtaken by the thought that they were using us as an

exercise target. Then from under the aircraft I could see a red burst,

and then there was a loud, dull thump and out of the corner of my eye

I saw it hit our bridge. My first thought was self preservation and I

moved to crawl under the gun platform. Unfortunately it was only about

three inches off the deck and I was a bit too large, so I tumbled down

the hatchway in the wardroom flat... Things went very quiet at this

stage, and I recall seeing one seaman with the lower half of his face

shot away.'

Lieutenant‑Commander Johnson in BRITOMART, the first to be hit:

'The

second lunch had been cleared away and the wardroom table was covered

with signals awaiting their turn. All officers not on the bridge ‑ and

this included the warrant engineer and even the sweep deck officer ‑

were in the wardroom deciphering the mounds of signals that kept

pouring in. We had our heads down to this task when two great

explosions shocked the entire ship by their power and violence,

smashing, shattering, shuddering. My immediate thought was that we had

been mined for'ard, but three seconds later, before we had time to

collect ourselves, two more explosions sounded under the quarterdeck

on the port side, muffled as though underwater. The ship lurched over

to starboard and rolled back to settle with a ten degree list to port,

the officers' cabins and alleyways having flooded instantly. Luckily

in the wardroom we were all sitting either on the bulkhead settees or

in low armchairs, not at the table, for at this moment cannon fire

raked the wardroom just above table level, smashing right through the

ship. We bundled out on deck only to fall flat on our faces when

greeted by a second bout of fire from an aircraft streaking past to

starboard ‑ we were horrified to see that it was an RAF Typhoon. It

wheeled round some distance astern and flew past us again ‑ our gunner

on the after Oerlikon let fly until. No. 1 yelled to him to stop. We

also recognized two other planes in the distance by the easily

discernible white bands on their wings.'

'The

realization that we had been attacked by friendly aircraft came as a

great shock. A double shock, for any attack at all had seemed most

unlikely with us steaming in the middle of a minefield, where no

U‑boat could venture, and with the air completely dominated by Allied

planes.'

'BRITOMART was settling quickly by the stern with an increasing list

to port and flooding fast. The magazine hatch on the sweep deck was

open and I saw two ratings who had been working there scramble safely

out of the water, but ominously smoke was also emerging. We could see

little of the rest of the ship because of dense smoke belching from

for'ard, then she started to swing to starboard and a breeze cleared

some of the smoke. The view that met our eyes was grim. No bridge,

only a smoking hole where it had been, and just forward another deep

smoking hole which had been the stokers' mess. The funnel had also

vanished completely and the main deck had burst open opposite the

fiddley, ripping clear across and making it impossible for us to get

for'ard ‑ we were isolated in the after part of the ship. The steering

gear had jammed to starboard and the ship circled into the minefield,

still dragging her Double L sweep wire which continued to pump out

5000 amps. We overtook our electrodes well before the ship lost way,

becoming exposed to any hungry mine.'

'The

engine took some time to stop. The Chief (Engineer Officer, Warrant

Officer J R D Grigson) ran on deck with an axe and cut off the tail

as a precaution ‑ he could have killed himself in an electrical

explosion. As the ship stopped our severed tail floated alongside.

BRITOMART now lay at an angle of thirty degrees and still deeper by

the stern. The No. 1, Lieutenant George Merritt, and I decided to

order "Abandon ship". We had difficulty in persuading some men to take

the plunge, though others had already gone over the side before the

ship stopped. All six officers including myself penetrated along the

decks as far as we could, urging men to jump overboard and in some

cases having physically to throw them into the sea. Some men were

wounded, two I tried to rally were dead. The ship's motor launch was

lowered into the water but it had not gone far before it sank with the

men inside, its bottom holed in several places by cannon shells. Our

burning ship was surrounded by bits and pieces of lockers, planks,

Carley floats and men swimming in their Mae Wests. One resolutely

cheerful rating who had helped to get others into the water now took

the plunge himself and, to the tune of "Mairzy Doats", began to sing,

"Motor boats and Carley floats and little rafts and dinghies..."

'We

were so busy trying to save the survivors among our crew that we did

not see any other ships, the rest of the flotilla had disappeared from

view, although we did see boats some distance away picking up some of

our swimmers. By chance we now found some spare life jackets which we

thrust to men who had been reluctant to jump because, against standing

orders, they had not been wearing their own. We quickly saw them over

the side, for the smoke pouring from the depth‑charge magazine was an

added incentive to be gone. The ship was capsizing rapidly and a

sudden lurch to forty‑five degrees sending away the last of the

reluctant swimmers, another officer and myself, having placed our

shoes neatly side by side on the sloping deck, stepped off into the

sea.'

Ernest Staniforth

My father Ernest

Staniforth,SSX25410 served on Britomart from 2/06/1941 to its sinking

on 27/08/1944. He very rarely spoke about his experiences during the

war as the sinking was very traumatic and he lost friends in terrible

circumstances. At the time of the attack he had just been taken of

watch in the wheelhouse and was down in the mess, the chap who had

taken him off was killed outright while at the the wheel. My father

ended up in the water with a mate who was injured, my dad swam with

him for a while in all the oil and flames, he eventually had to

abandon him as he had lost most of his lower torso and would not have

survived. He ended up ashore in an orchard in France and was

eventually rescued and taken to Dartmouth and sent on survivors leave.

(Source:

R. E. Staniforth (son) Oct 2008)

William

George Jenkins

was a crew member on

Britomart for the whole war until it was sunk. He was a "Leading

Writer" in charge of the ships administration. He escaped the burning

ship by swimming under the burning slick of oil despite a broken

collar bone and much shrapnel in his leg and some in his head. He was

invalided out after that from his injuries.

(Source: Georgie Tsyplek)

BRITOMART, still on fire, turned completely over and floated keel

upwards, but sinking by the stern. It had all happened in thirty

minutes. Her commander and thirteen others were killed when the bridge

was blown to bits by rockets. The dead included the officer of the

watch, the yeoman, wireless staff Asdic ratings, the quartermaster and

bosun's mate. Other men lay dead or dying. More than seventy of the

surviving crew members were wounded, some very severely.

Sketch made by

divers of BRITOMART 30 metres down on the sea bed in 2002

Position:

49°40.294N / 000°06.775W

www.grieme.org

Source: ADM 1/30555

tempy. lieutenant g merrett

rnvr

On the occasion of

total loss of HMS Britomart, 27/8/44

After ‘Abandon

Ship’ had been executed , Lieut Merrett remained aboard assisting

Lieut E J W Cooper and myself to remove a number of unconscious

ratings from the after deck into the sea, first providing buoyancy

to any who were negative lifejackets.

Two or three lives

were thus saved. I noticed a revival after their hitting the water,

and they were picked up later by H.M.T. Lord Ashfield’s boat.

Unfortunately the majority of the ratings that were disposed of in

this manner proved to be dead.

During the time

this work was in progress, the ship was ablaze fore and aft, the

boarding on the after magazine, situated below the quarterdeck. The

20mm ready use ammunition on upper deck was exploding spasmodically,

and the fire was uncomfortably near the primed grenade locker.

Lieut Merrett

displayed admirable coolness and courage.

Signed Harold Johnson, Act Temp

Lieutenant Commander, HMS Mandate

H M S Britomart Honours and Awards

The

Honours and Awards Committee has considered the good service of

Officers of H.M.S. Britomart and submits that the King be asked to

approve the Appointments and Awards set forth below.

When

HMS Britomart was on fire and sinking after being attacked from the

air Lieutenant Commander Johnson and Lieutenants Cooper and Merrett

did gallant service in removing a number of unconscious ratings from

the after deck into the sea providing buoyancy to any who were

negative life-jackets, thereby saving some lives.

O.B.E.

T/A/Lt.Cdr.

Harold Johnson, RNR

Mention in Despatches

T/Lt. Edward John Cooper, RNVR

T/Lt. George Merrett, RNVR

Signed Vice Admiral

Chairman, Honours and Awards Committee

17th

December 1945.

|

|

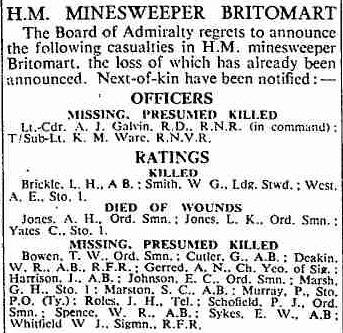

HMS

BRITOMART

21 Officers and men

killed on 27th August 1944 (includes 2 who died shortly

after) and there were 70 wounded

|

|

LAST

NAME |

FIRST

NAME(S) |

RANK |

SERVICE

NUMBER |

AGE |

FAMILY

DETAILS |

|

BOWEN |

Thomas

William |

Ordinary Seaman |

D/JX

570723 |

- |

- |

|

BRICKLE |

Lewis

Henry Hubert |

Able

Seaman |

D/J

104664 |

40 |

Son of

Mr and Mrs Jack Brickle; husband of Olwen Brickle, of Orielton,

Pembrokeshire, Wales |

|

CUTLER |

Gerald |

Able

Seaman |

D/SSX

24580 |

27 |

Son of

John and Florence Cutler, of Sneinton Dale, Nottingham |

|

DEAKIN |

William Richard |

Able

Seaman |

D/J

73416 |

- |

- |

|

GERRED |

Albert

Newton |

Chief

Yeoman of Signals |

D/J

90489 |

- |

Son of

Frederick and Margaret Gerred; husband of Miriam Esther Gerred, of

Shirley, Southampton |

|

HARRISON |

Joseph |

Able

Seaman |

D/JX

238295 |

23 |

Son of

James and Emma Harrison, of Hyde, Cheshire |

|

JOHNSON |

Ernest

Charles |

Ordinary Seaman |

D/JX

570743 |

19 |

Son of

Ernest George and Emma Louisa Johnson, of Horfield, Bristol |

|

JONES |

Alan

Hugh |

Ordinary Seaman |

D/JX

559094 |

19 |

Son of

Joseph and Alice Matilda Jones, of Risca |

|

JONES |

Leon

Kenneth Edgar |

Ordinary Seaman |

D/JX

559568 |

21 |

Son of

Leon Christopher and Eleanor Jones, of Newport |

|

MARSH |

George

Herbert |

Stoker

1st Class |

D/KX

147555 |

- |

- |

|

MARSTON |

Sidney

Clifford |

Able

Seaman |

D/JX

184868 |

24 |

Son of

Sidney William and Anne Ethel Marston; husband of Eileen Alice

Marston, of Richards Castle, Shropshire |

|

MURRAY |

Patrick |

Petty

Officer Stoker |

D/KX

86002 |

- |

- |

|

ROLES |

John

Henry |

Ordinary Telegraphist |

D/JX

610352 |

- |

- |

|

SCHOFIELD |

Philip

James |

Ordinary Seaman |

D/JX

570495 |

- |

- |

|

SMITH |

Walter

George |

Leading Steward |

D/LX

24871 |

36 |

Son of

John and Frances H Smith; husband of Joyce Lilian Smith, of Brimscombe,

Gloucestershire |

|

SPENCE |

William Robert |

Able

Seaman |

D/J

89495 |

44 |

Son of

William and Elizabeth Scott Spence; husband of Laura Ethel Spence, of

Plymouth |

|

SYKES |

Ernest

William |

Able

Seaman |

D/JX

304909 |

21 |

Son of

Joseph and Mary Ellen Sykes, of Manchester |

|

WARE |

Kenneth Martin |

Sub-Lieutenant |

- |

35 |

Son of

Frederick and Mabel Ware, of Taunton, Somerset; husband of Margery

Seward Ware, of Taunton |

|

WEST |

Albert

Edward |

Stoker

1st Class |

D/KX

152777 |

20 |

Son of

Thomas and Emily West, of Exmouth, Devon; husband of Barbara M West,

of Exmouth |

|

WHITFIELD |

William Frederick |

Signalman |

D/J

39682 |

|

Son of

Alfred and Ellen Whitfield; husband of Lena Whitfield, of Woodford

Greell, Essex |

|

YATES |

Charles |

Stoker

1st Class |

D/KX

140883 |

32 |

Son of

Charles and Annie Yates, of Liverpool |

|