Extracts from ‘No Day Too

Long’, G S Ritchie

With additional extracts THE WAR

OF THE HALCYONS 1939‑1945 R A Ruegg World Ship Society

On the

outbreak of war, two of the four Halcyon class minesweepers which

had been completed as survey ships, JASON and GLEANER, were taken

over by the general service. The latter, in command of a surveyor,

Lieutenant Commander Price, soon distinguished herself by sinking a

U‑boat in the approaches to the Clyde.

In early 1946

these two vessels were replaced by a single Halcyon class

minesweeper which had survived the War, SHARPSHOOTER. To this ship I

was appointed as first lieutenant to oversee her conversion to a

surveying ship, at Green and Silley Weir of London, and by mid‑1946

we were on our way to the Far East under the command of Commander

Henry Menzies, a gaunt figure with a zest for life and an insatiable

enthusiasm for new hobbies. He was a competent surveyor from whom I

learnt much during the next four years.

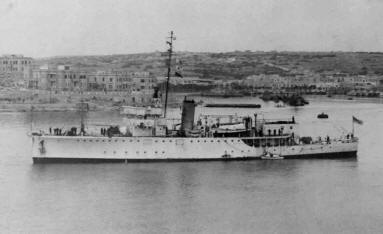

HMS Sharpshooter in Malta en

route to Far East

(Source: Steve Prigmore)

As she sailed east she performed a

small survey in the Aden area and continued on to Trincomalee via

Bombay. On 10 July she departed Trincomalee and carried out a short

survey in the Mergui Archipelago (S. Burma coast). (Ruegg)

On our way to

Singapore we were diverted to Mergui in southern Burma to survey the

shallow approaches so that supplies of rice could be brought in to

alleviate the hardship currently endured by the people of the

Tenasserim coast. Our main tasks, however, were based on Singapore

from where we were to conduct surveys on the East Coast of Malaya

and in Sarawak.

On 25 July 1946 she sailed for Penang to locate wrecks in

the southern approaches to the port. By 3 August she was at

Singapore from whence she departed on the 24th for a month's survey

on the Malayan east coast. She then had a short stay at Singapore

before sailing for a variety of survey duties to occupy her

commission. As these duties are outside the scope of the available

war records only a

brief resume will follow to cover her later years. (Ruegg)

HMS Sharpshooter in

Singapore, view of Chartroom (bottom right)

(Source: Steve Prigmore)

On arrival in

the Naval Base at Singapore the Flag Officer, Malayan Area,

requested that surveys of the small East Coast riverine parts of

Kuantun and Rompin be given priority so that much needed rice could

be shipped in for the natives of a remote area with few roads. It

was necessary to complete this work before the onset of the

north‑east monsoon, so while the ship underwent some minor repairs

advance parties were sent north by jeep. In previous years there was

no East Coast road, but the Japanese had constructed one. It was

little more than a track, whilst the rotting timbers of the many

bridges over the sungeis made jeep travel both laborious and at

times exciting. Unarmed, we slept happily in our camp beds in a

barnlike structure in the village of Rompin, heedless of the posters

adorning the walls denoting earlier Communist occupation. Within a

few months this was to become a no‑go area for Europeans.

Ten years

after surveying at Kermaman I was back at the site of our old

tidepole in the river. I located with ease our benchmark, which I

had cut in a massive boulder, and to which I levelled a newly

established tidepole to be read by a couple of tidewatchers

concurrently with the reading of a tidepole at Kuantun in order to

transfer our previously established datum from Kemaman. Some of the

villagers remembered our camp party; they had suffered much since

then during the Japanese occupation, and they told me that the

District Officer who had organised the building of our atap house in

1936 had been killed by the Japanese as they stormed southwards

towards Singapore.

Henry Menzies

always believed in testing his surveys with the ship, so we had a

thrilling passage in SHARPSHOOTER across the shallow Kuantan bar

over which the sea was breaking, followed by a 90°turn to starboard

into the river. We anchored off the small town of Kuantun dressed

overall for the King's Birthday and received onboard His Highness

the Sultan of Pahang a fitting end to our East Coast surveys.

The small

State of Brunei in North Borneo comprises land on either side of the

Sungei Brunei, the famed stilted village in the river, the town of

Brunei and the Sultan's Palace. The river is entered across an

extensive bar, the depths over which had not been checked since

prewar. This was SHARPSHOOTER's next task, during which a grounding

of the vessel on a sandy seabed was soon resolved by the use of

kedge anchors, the laying out of which I had already experienced in

both Herald and Endeavour.

Muara Island,

on the starboard hand as one enters the river is today, I

understand, the centre of a thriving oil industry and it is

difficult to believe that a rather stupid surveying recorder whom we

sent ashore to erect a mark on the island was lost for twenty‑four

hours in thick jungle.

Before

sailing for Brunei our medical officer was relieved by a stocky

young extrovert who came from Combined Operations together with a

motorised canoe he had 'liberated' and a number of other diverse

items. After a few days at sea the leading stoker in charge of the

mess, which was located in close proximity to the Sick Bay, asked me

if I could do something about a heavy sack which the doctor had

stowed beneath their mess table and required moving every time the

mess was scrubbed out. I bustled down to the mess deck and on

opening the sewn up sack I was surprised to find a truncated corpse.

I confronted the doctor who said that he had bought it from a

Chinaman in Singapore, it was heavily injected for preservation,

there was no room for it in the Sick Bay and he would be using it

for training his junior assistant. He did not take kindly to my

order to dispose of his precious body overboard, whilst the stokers

expressed some concern that the corpse of a Chinaman had been at

their feet as they took their daily meals.

In April 1947 we

sailed for Sarawak. Much had changed in this beautiful country since

the pre war Herald days of which I had so many happy memories……. When

we arrived in SHARPSHOOTER six months after the birth of the new

colony we found the people confused and divided, yet they clearly

retained much of the friendliness and charm I so vividly remembered

from the old days.

The British

Government's desire now was to open up their new colony and

stimulate trade, so in a country of very few roads our attention was

directed towards the improvement of commercial navigation along the

rivers. Herald, in pre war days, had surveyed the Rajang, Sarawak's

greatest river, as far as Sarekei, a small township thirty‑five

miles from the sea. SHARPSHOOTER's task was now to survey the river

for a further thirty‑five miles upstream to Sibu, the second largest

town in the country and headquarters of the Third Division. There

were a great many potential exports from Sibu including rubber,

pepper, chillies, timber, charcoal, palm oil, copra, jelutong (the

basis of chewing gum), rice and kutch (from mangrove bark, used in

tanning).

HMS Sharpshooter: boat deck

taken from bridge; forecastle and bridge.

(Source: Steve Prigmore)

The river,

which was ever busy with prahus coming and going, varies in width

from about 200 yards to a mile; for the first half of the passage to

Sibu the banks were fringed with a wide band of mangroves and nipah

palms, the leaves of the latter being used to thatch the Than (Sea

Dyak) longhouses which, built on high stilts, were to be

found at frequent intervals on either side of the river. Later a

smaller freshwater mangrove took over and more open country provided

space for the rubber gardens of the Foochow Chinese.

Little firm

coastline was to be seen on the air photographs with which we had

been provided. This dictated that the triangulation supporting the

survey would have to be carried upriver by single triangles rather

than balanced quadrilaterals, since the labour of clearing mangrove

would be disproportionate to the results achieved, whilst there

would be a chance to tie in our triangulation to the few Sarawak

survey traverse points along the way. Metre‑square collapsible

canvas covered marks were prepared by the shipwright which could be

hung in the mangrove trees beneath which a surveyor could position

himself in a folboat to observe the angles to similar marks

comprising the triangles.

HMS Sharpshooter in Borneo

Source: Steve Prigmore

The ship

anchored off Sarikei on 19th April 1947 to recover Herald's pre-war

benchmark and to establish the first of a number of tidal observing

camps which would be required to carry the tidal datum upstream.

Here we met our first lbans wandering through the few streets buying

necessities from the Chinese stalls. The men were stocky in build,

their thick black hair cut to a fringe in front; their throats,

their arms and their thighs were tattooed with strange asymmetrical

swirling designs. They wore the briefest of loincloths with a parang

in its wooden sheath secured with a rope of coconut fibre around

their waists, or thrust into the long creel‑like baskets which they

carried on their backs. Their womenfolk, who we were to encounter

later, wore only a sarong and were of comely shape and happy

disposition.

The western

mooring dolphin off the jetty at Sarikei had been coordinated by

Herald when terminating her pre-war survey of the lower Rajang and

so, to provide a starting baseline for our own work, a boat's

taut‑wire machine, such as Berncastle and Glen had used off the

Normandy beaches, was used to measure a distance up the first reach

of the river to a terminal station established on an accessible firm

area of riverbank; the direction to the dolphin was computed from

astronomical observations made with theodolite at this terminal. The

captain's ingenuity led us to work out a system that made the best

use of all the surveying officers and recorders and our boats, even

including the doctor's motor canoe, in order to carry the survey

upstream at a rate of one to two miles a day….

Unknown crewman, HMS

Sharpshooter

(Source: Steve Prigmore)

…Every two or

three days the ship was moved forward into the newly sounded area to

anchor nearer the scene of operations. By transferring the port

bower anchor, together with its swivel piece, to the 3˝ inch wire

towing hawser rove onto the port Oropesa winch, the ship was able to

moor head and stem in those narrower parts of the river where there

was no room to swing.

Those in the

advanced boats often spent their nights as guests in a longhouse,

thus avoiding a long upstream trip from the ship in the morning.

This was an unusual experience: throughout the night people came and

went across the creaking floors of the communal area, gangs left for

distant padi fields, groups returned from festivities in other

longhouses, unsteadily climbing the notched tree trunk, which led

from the prahu landing up to the house. Tuak, a sweet thick

alcoholic beverage distilled from rice was always in supply.

My

opportunity to spend a night in a longhouse came when Henry Menzies

moored the ship off Kampong Leman one afternoon and announced a 'hari

raya' (holiday) in honour of the King's Birthday next day. By early

evening a raft of about sixty prahus, reaching nearly to the

riverbank, was made fast to the gangway with about 300 Dyaks

squatting on the quarterdeck in readiness for the ship's film show,

in which a newsreel showing the Oxford and Cambridge boat race was

always well received with derisive shouts of 'kayu belakang'‑ or

‘paddling the wrong way round'; fortunately we also had a stock of

'Westerns' with plenty of shooting.

As night fell

a number of us, including Henry, went ashore for a party in the

nearby longhouse. Tuak was liberally served from the outset. We

admired the recently acquired stock of smoked Japanese heads hanging

from the rafters, and slowly the music began and dancing commenced.

Gongs in long wooden troughs, hollow logs and a variety of drums

were used to provide the music, whilst the dancing consisted of wild

posturings and swirlings by individuals or groups, the imitation of

which by the gangling figures of Henry and Charles Scott our senior

watchkeeper, brought shrieks of merriment from the women and

children. Time passes quickly when one is under the influence of

tuak and first light, announced by the crowing of cockerels and the

quarrelling of dogs beneath the longhouse, came all too soon. The

weary orchestra fumbled to a finish and our hosts assisted us down

the tree trunk and into the prahus for return to the ship and a

day's sleep.

Living

communally as they did, the lbans had no conception of privacy and

felt free to board the ship at any time and wander where they

pleased, a practice we did not oppose. Not one article of any

description was stolen during the five weeks it took us to reach

Sibu where SHARPSHOOTER berthed alongside on 1st July; during this

time we estimated we had played host to about 2,000 lbans….

.... For some

time it had been our captain's ambition to have a tame gibbon

onboard and this desire had been imparted to the lbans as we moved

up river. Just before we sailed from Sibu a message filtered through

that a gibbon awaited delivery in the vicinity of Binatang half way

down river to Sarikei.

I have

already mentioned Henry's love of ship handling. He had found that

in the rivers when going with the stream the ship almost steered

herself around the bends, whilst in the reverse direction canal

effect was absent, the current took the wrong bow, and it was

necessary to fight her round the bends. When the time came to sail

downriver from Sibu a great freshet was running bringing with it

huge tree trunks and great islands of vegetation. Henry was

delighted and set off downstream at a great speed, sweeping round

the bends with the minimum of help from the wheel, including the

120' turn at Leba‑an. As we approached Binatang all eyes were on the

prahus in search of the gibbon ‑ and, yes, there were four lbans

holding high a young black ape. The river here was narrow so the

decision was to anchor by the stem using the kedge anchor and lie to

the racing river waters for the transfer. I was sent to the bridge

to take charge of the ship, while Henry went to the quarterdeck to

receive the animal.

The kedge

failed to hold the ship in the strong current and we slowly dragged

downstream; only occasionally did I dare to use the engines astern

to slow our progress, fearful as I was of fouling the towing hawser.

Meanwhile the activities on the quarterdeck seemed unduly

protracted; however, at long last a smiling Henry returned to the

bridge, blood streaming from one of his fingers, but the ape ('never

call it a monkey,' said Henry) was safely belted and on its chain in

the cuddy.

Next followed

a visit to Singapore for fuel and stores before returning to

Sarawak, where a tide‑watching party was left on the small

uninhabited island of Pulo Lakei near the entrance to the Ktiching

River in order to transfer a tidal datum established there by Herald

to the Batang Lupar in the Second Division which was the next river

to be surveyed. On arrival next day in the Batang Lupar a

tide‑watching camp was established on the right bank about a quarter

of a mile from a Malay kampong near the entrance to the river.

Meanwhile a signal was received from the leading seaman in charge at

Pulo Lakei ‘Island swarming at night with giant iguanas stop Request

instructions' ‑ 'Carry a torch' was Henry's laconic reply.

The Batang

Lupar posed new problems. It was about two miles wide at its mouth

and the streams, apart from brief slack water periods, ran at

strengths between two and three and a half knots, making it

impossible to use any but the two sounding boats.

(Source: Steve Prigmore)

Henry had

wasted no time during the passage to and from Singapore in training

his gibbon and it was already extremely biddable and friendly. It

learnt to use the W.C., for peeing at least, whilst hanging by its

long arms from the deckhead, although it had not yet learnt to push

the flush!

It was

arranged that the Governor of the new colony, Sir Charles

Arden-Clark, whilst on a tour of the Second Division in his launch,

should visit SHARPSHOOTER in the Batang Lupar and take luncheon with

the captain whilst I joined the A.D.C. to make a foursome. Henry was

delighted at the opportunity to show off the gibbon, which was

restricted to the starboard side of the cuddy by its belt and chain.

After lunch, when seated in armchairs to take coffee, I noticed that

the gibbon, hanging by its arms from the deckhead, was fascinated by

the plume of feathers on the Governor's hat, on the table beside

him, which was being gently agitated by an overhead fan. Suddenly,

at the end of its tether, the gibbon aimed a copious jet towards the

ornate head gear. The effort fell slightly short of target but never

have I seen a vice‑regal visit so abruptly concluded as the coxswain

and quartermaster were rapidly assembled to pipe the 'Still' for the

Governor's departure.

On return

from a brief visit by the ship to Kuching I was despatched with

Petty Officer Slater, the coxswain, in a surveying motorboat to see

how the tide‑watchers were faring. At the tidepole among the

mangroves we found a crude notice affixed to a tree ‑ 'Gon Kampong

back soon, Abang.' Within five minutes, on nearing the hour, a young

Malay carrying the 'Record of Tide Readings' book emerged from the

soggy pathway. He was taken aback when he saw us but nevertheless

composed himself sufficiently to record the hourly tidepole reading

before we started to question him as to the whereabouts of the

leading seaman and his two fellow tide‑watchers. He indicated

haltingly that as 'Charlie' was getting married to an upriver Dyak

woman the whole party had gone for the celebrations, leaving him in

charge of the tidepole. Informing the ship by radio of these

surprising developments we set out upriver against a strong ebbing

current. In time the first longhouses appeared, deserted except for

a few old men and women who waved onwards whither the young people

had gone to celebrate. After three or four hours of travelling we

heard a distant cacophony of gongs, drums and the human voice which

led us eventually into a backwater and to a longhouse alive with

activity and merriment. Seldom have two uninvited guests been so

unwelcome at a wedding party. Refusing offers of roast pig and

foaming tuak we arrested the three absentee tide‑watchers, dressed

in sarongs, their heads bedecked with flowers, whilst the young

bride clung to Stoker Charlie Ledger weeping copiously. It was dark

long before we reached the ship with our deflated captives who were

charged on arrival with being absent from their place of duty,

perhaps a less serious crime than desertion which could equally have

met the case.

Charles

Ledger, a 'hostilities only' rating, had, like a number of others

onboard been keenly awaiting news of his discharge. As a former

Yorkshire miner he had received priority, and orders to arrange an

immediate passage for him to U.K. had been received onboard during

the recent visit to Kuching. There were some sad days in the river

when daily the young bride and her mother arrived alongside byprahu

and were allowed to converse with Charles, who was confined to the

ship, from the quarterdeck. Meanwhile messages between the ship and

the authorities in Kuching elicited the fact that a marriage of this

nature was not recognisable in law, and the hope must be that,

as Ledger returned to the coalface, his Dyak bride found a more

suitable husband to provide for her in the jungles of Sarawak.

There was no

particular task for the doctor in the survey of the Batang Lupar so

he spent most of his days lying on the bridge chart table enduring

the daily increasing pain as a Dyak tattooist tap‑tapped with a

hand‑held needle to impose a native tattoo on his shoulder. Only

tots of brandy brought to him by his fellow Idlers enabled him to

see the work completed……

…..When

SHARPSHOOTER had sailed from England in May 1946 we were told that

we should be away for a limited period until we were relieved by

Dampier, the first of four Bay Class frigates which, with war ended,

were being completed as survey ships. At long last news of Dampier's

completion was received and we realised that with luck we should be

home a few days before Christmas after eighteen months' absence.

There was,

however, one last task to be tackled. Port Swettenharn, the port

serving the capital of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, was now quite

inadequate for post‑war trade and plans had been drawn up for the

establishment of extensive wharves in the closely adjacent North

Klang Strait. The Strait was bordered with a wide and ancient

mangrove forest. Here the scale of the survey for the port

development was large, necessitating a second order triangulation to

be carried through the swamps where 'jet propelled clearers' were

unavailable. So we had to clear lanes ourselves up to half a mile in

length; many days were spent either up to our waists in water or

knee deep in mud as we hacked away at the iron‑hard mangrove trees

with an assortment of axes, choppers and parangs, nightly

re‑sharpened by the shipwright. Eventually the sightlines were

clear, platforms were built above the mud to facilitate theodolite

observations, the triangulation was balanced and plotted and the

work of sounding North Klang Strait completed.

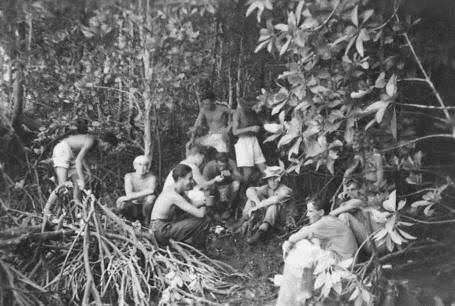

Crew of HMS Sharpshooter in the

jungle - Malaya

(Source: Steve Prigmore)

Henry had

found a good home for his gibbon with friends in Singapore, and for

the long voyage home he turned his attention to rug‑making devising

his own pattern of a bluish grey Dyak tattoo on a brown skin

background. By the time we reached Chatham a magnificent and unusual

hearth rug adorned the cuddy. In front of the bridge the ship

carried a great wooden carved and gaudily painted 'Kenyalang', the

mythical bird of good omen of the Borneo jungles, to remind us, had

that been necessary, of our life among the lbans of Sarawak.