|

|

|

Date of Arrival

|

Place

|

Date of Departure

|

Orders, Remarks

etc |

|

4.1.42

|

Murmansk

|

? |

|

|

12.1.42 |

|

|

BRAMBLE, Hebe and

Hazard rendezvoused with PQ7 and brought this convoy into Murmansk

|

|

24.1.42 |

Harrier and Speedwell form part of eastern local

escort for QP6 (6 ships) from 24/1 until 25/1. BRAMBLE and Hebe joined

on 25/1 along with the cruiser Trinidad and the destroyer Somali, and

remained until 28/1 when the convoy dispersed. |

|

31.1.42

|

Scapa

|

5.2.42

|

1/2

From C in C Home Fleet: Concur

From

HM Admiralty: Vessel to be taken in hand for arcticising and

concurrent refit by Greenwells of Sunderland at earliest possible

date. |

|

7.2.42

|

Sunderland

|

11.4.42

|

7/2

From FO i/c: BRAMBLE is being taken in hand at Greenwells Sunderland,

completes 21/2.

12/3

Provisional date of completion will be 10/4

From

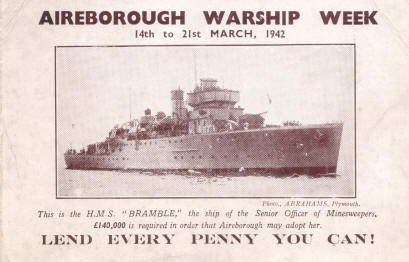

March 14 1942 until March 21 1942 was Warships Week and the people

of Aireborough raised £140,000 to 'pay' for BRAMBLE. Captain Crombie

and members of the crew visited the town, presenting a plaque to the

Aireborough Savings Committee (which can still be seen

in

Saint Oswald's Church, Guiseley).

(A memorial service was held at Saint Oswald's after the loss of

Bramble and her crew.)

|

Photos Source: ADM 176/873

|

Date of Arrival

|

Place

|

Date of Departure

|

Orders, Remarks

etc |

|

11.4.42

|

Tyne |

12.4.42

|

|

|

13.4.42

|

Scapa

|

23.4.42

|

15/4

From RA (D) Home Fleet:- It is anticipated that S.O. 1st MS

in BRAMBLE with Seagull will be available to escort PQ15 from

Reykjavik

.

!7/4 Kenneth George

Edge, Sick Berth Attendant, died age 25

Received 22nd April 1942

Proceed with BRAMBLE, Leda

and Seagull passing Switha 1300 tomorrow Thursday to Hvalfjord routed

through position 58.49N, 06.59W , thence direct to Reykjames passage.

BRAMBLE, Leda and Seagull will act as escort to Convoy PQ15. |

|

|

Source: ADM 199/721

Report of Proceedings Period 23rd April

to 5th May 1942 (Extract)

From: The Rear Admiral Commanding, 10th

Cruiser Squadron

Date: 6th May

1942 No.217/0608

To: The Commander in Chief, Home

Fleet

The following report of proceedings is

submitted:

2. In accordance with your signal times 1503/22nd

April, HMS Nigeria, wearing my flag, sailed from Scapa pm 23rd

April to Hvalfiord, preparatory to covering the passage of convoy

PQ15 to North Russia.

3. During the passage to Iceland the weather was

fine and clear enabling A/S air patrols to be flown.

4. The Captain, 1st Minesweeping

Flotilla, in Bramble (with Leda and Seagull in company) was met on

passage and I instructed him to increase speed in order that he

might reach Hvalfiord in time to attend the Convoy Conference. As

Senior Officer of the Close Escort it was most important that he

should be present and as a result of proceeding at best speed he was

able to arrive soon after the conference had started.

5. I consider that on every occasion it is

essential to the security of the convoy that Commanding Officers of

the Convoy Escorts should attend this conference and have requested

Rear Admiral (D) to sail future escorts accordingly....

|

|

25.4.42

|

Iceland

|

26.4.42 |

26/4

BRAMBLE (Captain J H F Crombie DSO RN and Senior Officer Escort) with

Leda and Seagull left Iceland as part escort to PQ15 (50 ships) |

|

26.4.42 |

PQ15 sailed from

Reykjavik on 26/4 with BRAMBLE, Leda and Seagull as part escort. |

|

2.5.42 |

Heavy escort left

the convoy and Capt J Crombie of HMS BRAMBLE became senior officer of

the escort.

CLICK HERE for Bramble's Report on

Convoy PQ15

At 2009 Seagull

(Lt Commander Pollock) with the destroyer St Albans attacked and

brought to the surface a submarine later identified as the out of

position Polish submarine Jastrzab. She was sunk by gunfire.

(See 'Seagull 1942' for details) |

|

3.5.42 |

At 0127 convoy

PQ15 was attacked by 6 He111’s at low level, sinking 3 merchant ships

with their torpedoes. 137 survivors were picked up. Three aircraft

were shot down.

At 2230 the convoy

was bombed by Ju88’s scoring one near miss for the loss of one

aircraft. |

|

4.5.42 |

In the evening a

south-easterly gale blew up off the Russian mainland, filling the air

with snow clouds and concealing the convoy. |

|

5.5.42 |

2100

BRAMBLE arrived Kola Inlet with PQ15. |

MESSAGE 2300/B 5th May 1942

From SO 1st M S Flotilla

PQ15 arrived Murmansk. Regret to

report loss of Botavon, Jutland, Cape Corso as a result of attack by

six torpedo aircraft at 2327 May 2nd in position 73N, 19.40E. Attack

carried out in good conditions and aircraft appeared to be led in

well by leader who may not have carried torpedo. Indications that

shadowing submarine may have surfaced and fired torpedoes at same

time. One aircraft destroyed and possibly one other. 136 survivors

including Commodore. Convoy bombed at 2230 May 3rd in position 73N,

31.51E. Minor damage from near miss to Cape Palliser only. One

Junkers 88 shot down. Attack badly carried out and hampered by low

cloud. Convoy continuously shadowed by one or more aircraft and or

one or more submarines to 36E. Submarines driven off successfully by

screening force forcing them to dive and firing depth charges in

vicinity. |

|

Date of Arrival |

Location |

Date of Departure |

Orders, Remarks etc |

|

? |

Kola Inlet

|

21.5.42 |

|

|

21.5.42 |

At sea |

23.5.42 |

Eastern Local Escort for QP12 comprised BRAMBLE, Gossamer, Leda,

Seagull and two Russian Destroyers. Harrier was part of the ocean

escort arriving Reykjavik 29/5 without incident. |

|

29.5.42 |

On

the evening of 29/5, 140 miles NE of the Kola Inlet, Captain Crombie

commanding the 1st MSF based at Kola joined convoy PQ16 in

HMS BRAMBLE, together with Leda, Seagull, Niger, Hussar and Gossamer.

The convoy divided and at 2330 Crombie’s section, escorting six of the

merchant ships to Archangel, was attacked by 15 Ju88’s while 18

attacked the Murmansk-bound ships. |

|

30.5.42 |

Crombie’s

division, proceeding in line ahead and led by the Empire Elgar,

arrived at the estuary of the Dvina on 30/5 where it met the ice

breaker Stalin. They began a passage through the ice lasting 40 hours.

Confined to the narrow lead cut by the Stalin, they were attacked by

Ju87 Stukas in a noisy but useless attack. This section of PQ16

passed Archangel and secured alongside at Bakarista, a new wharf two

miles upstream. |

|

|

The soviet icebreakers Krassin and Montcalm were escorted to Archangel

by HMS BRAMBLE, Leda, Hazard and Seagull. HMS Intrepid and Garland

were sailed later to act as cover against possible surface attack. The

whole force arrived at Archangel on 21st June. |

|

21.6.42

|

Murmansk

|

|

Escorted soviet Icebreakers to Archangel

with

Leda, Hazard and Seagull. |

|

26.6.42 |

At

sea |

|

26/6

BRAMBLE, Hazard, Leda and Seagull (left 28/6) provide local escort for

departing QP13 (36 ships). Niger and Hussar were also included as

through escort. |

|

29.6.42 |

|

|

The

tanker Hopemount sailed for Port Dickson with a heavy escort of two

icebreakers and nine other escorts including BRAMBLE, Hazard, and

Seagull. At the edge of the icepack the escorts turned back leaving

Hopemount and the icebreakers to continue towards the Pacific by the

northern route, fuelling soviet escorts and merchant ships, turning

back on 18/9. |

|

30.6.42

|

Archangel

|

? |

At

67.27N, 41.20E HM Ships BRAMBLE and Seagull carried out a successful

attack on a U-boat. CLICK

HERE

to see report.

BRAMBLE and Leda rounded up and escorted survivors of PQ17 into

Archangel, arriving 11/7 |

|

11.7.42

|

Dvina Bar

|

? |

|

|

22.7.42 |

BRAMBLE, Hazard,

Leda and four other ships met some of the surviving ships from PQ17

and escorted them into Archangel, arriving on the evening of 24/7.

|

| |

|

|

Source:

Extracts from ‘PQ17’

by Godfrey Winn who travelled to North Russia aboard HMS Pozarica

…..just before we

reached the juncture of the White Sea with the Dvina

River, we were met by the BRAMBLE, the flotilla leader of fleet

minesweepers based on North Russia.

We

knew nothing yet of their magnificent work, and like many other

introductions (and first impressions) this nearly went astray. Her

Captain hailed us in what seemed to our sensitive ears a rather

patronizing voice. "What was your bag?" As though we were just

returning from the moors after a pleasant day's shooting, to a log

fire, and buttered toast, and whisky and soda for those who liked

their tea that way. Bag. Bag. Bag. How could we explain the price of

every plane we had brought down to someone who hadn't been there? It

was all very well when Halcyon signalled earlier, 'Junkers

shooting is in season'. She was one of us. Whose was this

imperative, so pusser voice?

It

belonged to someone who later became my friend and ally, Captain

Harvey Crombie, DSO. I visited his home in Hampshire only last

week‑end and yarned till long after midnight about the bare‑faced

landscape of North Russia, and we smiled a little ruefully at some

of our memories, but most of all that I should have so hated that

morning the first sound of his voice through a loud‑hailer:

especially when he went on to inform us, laconically, that a pilot

to take us down the river might appear in five hours, five days,

five years. Of course, he was only trying to break in the new boys

gently. But we were past jokes. We wanted only one thing at that

moment: the curtain to come down on this Act.

HMS BRAMBLE during PQ17 (Godfrey Winn)

|

| |

|

25.7.42

|

Dvina

|

29.7.42

|

|

| |

|

|

Godfrey Winn was a regular visitor

to the wardrooms of the other ships in North Russia while waiting

for a return voyage to the UK. Many of his observations and

reminiscences about BRAMBLE give a rare first-hand insight into both

the men and the conditions in North Russia and are

therefore reproduced below in detail:

...Now

it was Captain Harvey Crombie, who was speaking. "We have been out

here nearly a year; we have, I think, shown the Russians that we

mean business and are a competent flotilla, but the situation

doesn't change as regards personal relationships. There is an iron

curtain, and I warn you seriously against any attempt to pass behind

it. Indeed, I think you were lucky to get away with it on shore

yesterday, for it may interest you to know, Winn, that not long ago

I was arrested myself and spent a very uncomfortable six hours in

the local lock‑up."

My

own Captain (of the Pozarica), being of equal rank with the speaker, looked suitably

shaken by this admission. "Not too much vodka, I hope?"

"No, but that reminds me when you go to one of their parties, as

you're bound to do, your only hope of survival is to eat masses of

butter between each glass of the stuff. I was told the tip, and it

really does serve as insulation. You'll have to drink whether you

want to or not, because if you don't, they think you're a sissy. To

them the height of hospitality is to get you under the table, and

that's the only kind of fraternization they will tolerate, the

Services getting together en masse ‑ no women, of course ‑

and believe me it can be an awful headache as most of us found last

winter at Murmansk. He put down his glass and lit another cigarette.

"You see, after the party is over, you're back exactly where you

were before. It hasn't advanced the general position at all. You're

no nearer understanding each other on the ordinary level. I'll give

you an example of what I mean. A tiny incident, but in its way more

revealing than whole books that could be written on the subject of

Anglo‑Soviet relations. Whenever I went ashore at Polyarnoe, I used

to wear galoshes, and one day I lost one of them in a snow drift. I

forgot all about it, produced another pair, and then months later,

when the thaw set in, I was summoned one day to the presence of

their Admiral, who informed me, through the interpreter, that

something of mine had been found. He sounded so serious I thought

some piece of damning evidence was about to be laid on the table

between us. Instead it was my galosh that had turned rip! But

they didn't think it a bit funny. Not a smile. Only at their

'blinds', after several hours of steady drinking, will you get a

flicker of recognition that we are all human beings made to a

similar pattern, fighting a common battle together, and both up

against it badly at the moment. So my advice to you, Lawford, is eat

butter ... but don't talk butter. Don't mince words. When I first

arrived, I found they knew about as much about the technical side of

minesweeping as the man in the moon, but I soon discovered that they

respect you if you make a bloody row. They think you are in earnest

which, God knows, we are. They have no use for soft soap diplomacy

and I respect them for that, but all the same ...”

"You'd prefer them not to chuck you into cells!"

"Oh

yes, of course, I started to tell you about that. Well, the other

day we organized a flotilla regatta here in the river. You know the

kind of thing. Whaler races and so forth. Anything to try and keep

the men happy as the leave situation is so tricky. Well, I changed

into mufti, as one does, to make things a little more free and easy,

and after watching the show I went for my usual evening walk, when

we are in harbour, along the wood‑piles. I'd done it the night

before, I did it the night afterwards, but would you believe it, I

had hardly got out of sight of the ship's moorings, when a young

Soviet sentry ‑ I should think he was about sixteen ‑ popped out on

me from behind the wood‑piles and arrested me on the spot. Of course

I produced all my paraphernalia, but it was no use. I was not in

uniform. Passes meant nothing to him, he couldn't read. So he

proceeded to march me off at the point of his bayonet and I was shut

up in a filthy little room while, presumably, the Commissar was sent

for. I thought at first: best to stay quiet, they can't keep me here

long . . . but in the end after several hours of flapdoodle, my

patience vanished, I completely lost my temper and gave them a full

calibre shot, which immediately produced results. That's what I mean

about standing up to them, because don't imagine that soft words and

sweet smiles will cure them of this ingrained suspicion and distrust

towards us.

Extracts from ‘PQ17’

by Godfrey Winn who travelled to North Russia aboard HMS Pozarica

|

|

29.7.42 |

The tanker

Hopemount sailed for Port Dickson with a heavy escort of two

icebreakers and 9 other escorts including BRAMBLE, Hazard, and

Seagull. At the edge of the icepack the escorts turned back leaving

Hopemount and the icebreakers to continue towards the Pacific by the

northern route, fuelling soviet escorts and merchant ships, turning

back on 18/9. |

|

|

Captain Crombie said “…I hope most sincerely, for your sake, that

you will not be stuck here long. Otherwise you'll be adopting

favourite verse as your signature tune, also:

“Let us then be up and doing

With a heart for any fate

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labour‑and learn to bloody well wait."

I

could tell from the twinkle in his eye that the emphasis he put on

the last line was meant to dissolve the seriousness of the

discussion into laughter: part of the man and his make‑up: part of

many Englishmen and their make‑up: part of a refusal to allow any

conditions, however trying, to destroy your sense of balance, your

ironic delight in self‑mockery as an aseptic corrective to any

tendency towards sermonizing. I think it was at that moment that my

respect and admiration for them all was born ‑ this little group of

exiles, whose work had been completely unpublicized ‑ even as I

realized that in an hour's talk not one word had been said to

suggest the extreme severity of their own life out there, their

living conditions during the long months of complete darkness, when

it was a commonplace for the thermometer to register between

eighty and ninety degrees of frost. True, it was summer at last ‑ a

brief few, weeks ‑ and there was daylight, but another winter lay

over the horizon, and as though he sensed the questions hovering on

my lips, Captain Crombie added quickly: "Now, you're a literary fella. Perhaps you can tell us the author of that quotation?"

"What, of the last line?" I countered, not wanting to commit myself.

(Longfellow or?)

“Oh, we all wrote that didn't we?" he said smiling, and

including the other guests seated round the table, especially the

commanders of such of the First and Sixth Flotillas of fleet

minesweepers which happened to be alongside at that moment. All

those who found themselves chance neighbours so far from home had

come in a body to pay their respects and sign their names in the

visitors' book of the Pozarica's Captain, and I was looking

through the book the other day to make sure who had been there that

evening ‑ Lt. H. J. Hall, Lotus ... Lt. Boyd,Poppy . . . Lt. Rankin,

Dianella . . . Lt. Bidwell, La... Lt. Wathen, Lord

Austin ... Banning, Rathlin, Master and one of them had

added “PQ17, Novaya Zemlya, and Ekonomia, and quite enough!" ‑ but,

in the end, after much reminiscent search, I could only be certain

that the three signatures which came to mean most to me personally

during our incarceration in North Russia were those of the

commanders of the Leda, Halcyon, and Hazard.

Three very different types of men: Seymour of Hazard, who had

just been awarded his brass hat, possessing an aquiline profile and

a passion for the R.N. that made his ship a model of efficiency and

his manner at first slightly intimidating till one came to

appreciate that if you are compelled by Service obligations to spend

years of your life, first in China, then in North Russia, it is as

well to adopt a creed of self‑sufficiency: Wynne‑Edwards, ruddy

cheeked, hospitable, warm‑hearted, whose ship, Leda, became

such a second home to me out there that I cannot even now think of

her and her crew without my heart contracting: and finally

Corbett‑Singleton of Halcyon, like a huge sheep‑dog with a

shy, sleepy manner, that did not prevent him from winning a double

D.S.C. in the course of the war, or from sending ‑ a lightning flash

of relieving humour - my favourite signal of the whole voyage. Just

as the news had been passed from ship to ship that our convoy had to

scatter, he hoisted, "Now I know what the Itie fleet feel like!"

Now

I know myself, because I have made it my concern to sort it all out,

something of the exploits of these two flotillas that first became

discs on the operational maps when they commenced their shuttle

service, accompanying the second convoy to make the trip through the

Barents Sea. That was in October, 1941, the flotilla leader,

BRAMBLE, was there, and from that time on no convoy made the

journey either way without at least two or three of this

small group as part of their escort the whole voyage. I, think it

was only when I found myself, later, a member of the crew of the

Cumberland serving in those same waters, in winter, that I

became in the least degree cognizant of what it must have been like

for ships, by comparison so tiny, facing exactly the same hazards,

with an inevitably minute proportion of the same resources to combat

not only the ravages of the weather but all the other dangers that

surrounded them.

On

one of their cabin walls I found hung up a kind of Christmas card

with an enscrolled text. Oh God, be good to me, because Thy sea

is so large, and my ship is so small. I did not fully understand

the need for this prayer when I first explored the living space of

these ships: the wardroom was pleasantly spacious, the Captain's

cabin on the upper deck compared favourably with the one I had come

to know so well: yes, I was told, there is room enough below for

every man to sling his hammock: but ... that admission on the cabin

wall came to have a new meaning for me when I asked Captain

Sherbrooke, who won the V.C. for the manner in which he brought yet

another convoy through to Russia, at the end of 1942, if he could

give me any details of the loss of the BRAMBLE that had been

with him at the time when four enemy cruisers came into the attack.

It happened we were fellow guests at lunch, the next summer, in the

panelled dining‑room of a country house, so far removed in

atmosphere from the action of this book. But I had to be sure if

there was anything more to know than that she was swallowed up with

all hands in the blackness of the winter's night. My neighbour

looked away towards the windows and the massed herbaceous borders,

flowering in all their beauty and all their colour that you miss so

dreadfully at sea. He shook his head and then added slowly, "No,

there was just a sudden flash of light on the horizon and that was

all . . ."

…..

It must be put on record, too, that the Russians possessed none of

the latest minesweeping gear, and even if they had, were not

sufficiently sea‑animals to employ it properly without supervision.

They had to be taught about degaussing, magnetic mines, Oropesa

sweeps. And while the teaching went on the sweeping went on also.

Indeed, if it had not been for our flotilla's efforts, the White Sea

would have been quite impassable to allied shipping and the Northern

route would have been closed for the duration. Just to keep the

channels clear of the constant mine‑dropping aircraft sorties was a

whole‑time job, under reasonable conditions. But the conditions were

not reasonable. Pack ice a hundred feet high was a commonplace the

more vicious battle was with the elements. As for the darkness, for

nine months in the year it was as much their waking as their

sleeping companion. "For your sake, I hope you will not be stuck

here long." M.S.1, as he will always be known to every man under

his command, had spoken those words in his usual pusser voice,

without emotion, without feeling though I do not doubt he was

visualising another winter's approach just round the bend of the

river. We were temporary visitors against the wood‑piles: their

ships were fast becoming part of the barren landscape, and though

they refused to allow the darkness and the isolation to diminish

their morale, they could not prevent the perpetual night from

playing strange tricks with their eyesight and inducing a physical

lassitude. This they fought by deliberately increasing their time at

sea, until their knowledge of "local conditions" was such that when

the sailed forth to meet the incoming convoy, the senior naval

officer in charge would always have the sense and the faith to allow

M.S.1 to lead the merchant ships his own way into harbour, even if

it entailed a detour into the ice as the safest protection against

the stepped‑up attacks of the German subs, now finding the Barents

Sea a more profitable hunting ground than the Atlantic. The

BRAMBLE's captain drew attention to his galoshes: the reason for

the DSO ribbon on his tunic I had to discover for myself. And I

discovered, too, how far from infallible first impressions can be.

As it happened, in our case, through the scattering of the convoy,

we were far down into White Sea before we had our first meeting.

Otherwise I should doubtless have had a different reaction to that

laconic, casually shouted greeting of, "What was your bag?"

Source: Extracts from ‘PQ17’

by Godfrey Winn who travelled to North Russia aboard HMS Pozarica

|

|

? |

Dvina

/ Archangel

|

22.8.42

|

During August the sweepers’ duties included a nightly watch for mines

dropped by enemy planes. |

|

23.8.42

|

Kola Inlet

|

24.8.42

|

HMS BRAMBLE (MS1), Seagull,

Hazard, Salamander, Blankney, and Middleton arrived from Archangel at

2300 on 23rd August bringing about 402 survivors with them including

30 hospital cases.

On account of the

increasing air activity in the Kola Inlet, the prospect of having

these ships here was not one that I enjoyed. Their arrival was timed

for the darkest part of the night (it is still light enough to read a

newspaper between 2300 and 0100 in clear weather) when German air

activity was at its lowest, allowing the safe transfer of survivors

and stores. After completing their

transfers the four Halcyon minesweepers moved out to

'hide' under Kildin Island before daylight.

Report of SBNO North

Russia Aug 1942 |

|

|

…"Do you think you could rake up a tin of any sort that is

different, for lunch?" He (the captain of the Pozarica) didn't care

for himself. It was the only time he ever asked, but he had Admiral

Bevan coming to see him. The S.0.N.R. had turned over his command to

Admiral Fisher, and was waiting transport home, resting meanwhile,

an anonymous guest ‑ if you can be anonymous with all that gold

braid‑in one of our own merchant ships, lying at Ekonomia.

I

passed him coming towards our ship. A man with grey hair and a

sensitive, gentle face. He looked very tired, I thought. I was going

out to lunch, too. M.S.1 had invited me to take "pot luck" and I was

wondering all the way along the quayside what the main dish would

be. It turned out to be bully beef fritters!

"How's Admiral Bevan going home?" I asked M.S.1 (Captain Crombie)

with a sigh.

“They're sending a Catalina for him."

"I

wish there was room for me in the plane."

The

words slipped out involuntarily and the next instant I was ashamed

of them. My host was looking at me keenly with his very blue eyes.

He seemed about to make a suggestion and then changed his mind. "I

suppose you find it rather difficult with so much time on your hands

and nothing to do.”

"Very." Then, in case he should misunderstand the one curt

monosyllable, I added: "I love the Pozy and all the people in her

more than I shall ever love any ship, but when we're alongside like

this, week after week, I don't feel I fit in –“ I was going to say

"belong" but altered the word at the last minute " ‑ as I do when we

are at sea. Besides, I am Iong overdue for the

Ganges.

I've probably been posted as a deserter now. And I've got this big

story."

“For your newspaper?"

“For the Admiralty, too. An eye‑witness account. After all, I am a

reporter."

He

nodded, judiciously, a captain sifting the evidence at ‘Defaulters'.

Off Caps. I was very conscious of the defensive note in my voice and

looked away, about the cabin, at the usual set of photos on the

writing‑desk, in the usual sort of Asprey frames. Only in this case

the wife was young, and the children were still small. And unlike

the other cabin there was a copy of The Times laid out, too,

which I picked up later, when we were having our coffee. To my

surprise it was dated long before our sailing from Belfast. As

though he could sense what was in my mind, my host said quietly:

"When the mail does I arrive ‑ and for obvious reasons there has

been quite a gap lately ‑ hand over the whole bundle of Times

to my steward and Jones then brings me one with my breakfast

every morning. You know there is not really much difference. The

correspondence column is the same and the fourth leaders have been

better than ever lately."

"I

don't know how you all stick it out here," I blurted out. M.S.1

raised his eyebrows. It was a gesture of some formidableness for

they were very bushy ones. He was a man of about forty with a big

head which dominated his body. You could not imagine somehow his

ever having been of lesser rank .. a midshipman, fresh from

Dartmouth, joining his first ship, the Q.E. But it had been

emphasized by my new friends in the flotilla how popular M.S.1 was

with the men under his command. He only barks when he really means

it, they said. And a matlow likes that, I was to learn later: what

he hates is what P. O. Hynes called "flannel".

“ I

mean, the monotony must be so awful," I added, watching the eyebrows

with some apprehension. "You forget, Winn, that your matlow is the

most adaptable creature in the world. I don't care to what country

he belongs. It is something in a sailor's blood. Look how they have

transformed the quayside here in a moment. You see, they are used to

long periods of exile, in peacetime, too. 'Going foreign', we call

it. And yet however foreign to their way of life is the corner of

the seven seas in which they find themselves, still somehow they

manage to preserve their own personality, and come up smiling,

clean, and good‑tempered."

Extracts from ‘PQ17’

by Godfrey Winn who travelled to North Russia aboard HMS Pozarica

|

|

25.8.42

|

Archangel

|

? |

|

|

12.9.42 |

“…

You are sailing about noon. I did not tell you before, in case it

fell through.” (Captain of Pozarica)

An

operation was pending. The American cruiser Tuscaloosa was due to

reach Kola Inlet that night, to take back as many of the wounded and

survivors as possible….

“M.S.1 and I put our heads together as soon as we heard. I did not

want to raise your hopes too soon, but he is to be Senior Officer of

the operation this end, his flotilla is helping to take all the

passengers up from Archangel to Kola, and he very sportingly has

offered to try to find you, if possible, too. It’s a gamble of

course. Every ship going home is bound to be dangerously

overcrowded.”

It

was a calm and beautiful afternoon: by far the most pleasant day

since our arrival at Ekonomia: gone, the molten sky: gone the low

cloud‑level, pressing ever down upon the pulses at our temples:

there was real blue in the heavens and the river, even when it

broadened out into the White Sea, remained as placid as the upper

reaches of the Thames. Once again a day for “getting brown for

leave", and the decks of the BRAMBLE were crowded with an

assortment of Merchant Navy personnel first and second officers

mostly, but dressed in shipwrecked, scarecrow clothes that concealed

all rank. But nothing could conceal their deep spring of excitement

to be at sea again and sailing in the right direction. They crammed

themselves together against the rails of the quarter‑deck, just

chewing the prospects ahead, and stripping down to the waist, many

of them, as though the touch of the sea‑air against their skins had

in itself some magical quality that would cleanse their minds as

well as their bodies of all the squalor of the bread line.

I

squeezed down in a corner against a bollard and closed my eyes. You

learnt that in war: to sleep while the going was good. I do not know

how long I had been in a semi‑conscious, drifting state when I must

have felt that someone was standing between me and the warmth of the

sun. I looked up, and there was the Captain's secretary, a boy with

bright gold hair and the face of an undergraduate in his first year

at Oxford.

"Hello, Culley. Does M.S.1 want me?"

"No, but he asked me to give you this. It's something he said when

he spoke to all the flotilla one Sunday when they were in harbour

together."

David Culley squatted beside me and took off his naval tunic, to

sunbathe, too. Now in his open tennis shirt and grey flannel

trousers he was an undergraduate, even to the small leather book in

his hand which he opened and I was so curious to know its contents

that I forgot about the piece of paper till much later.

"Do

you read much poetry?" I asked.

“I

do, as a matter of fact. It makes the dog‑watches pass more quickly,

out here. I even try to write a bit. I know most of A Shropshire

Lad by heart," he went on quickly. “ Actually I come from that

part of the country myself.”

“The Cotswolds ?"

"Yes"

“So

did I originally. It's wonderful, unforgettable country, isn’t it?

Do you know the view from the top of the hill above Broadway as well

as from Bredon? How many counties is it you are supposed to be able

to see there ... eight ? ... I always forget but I keep on promising

myself to go back there ... as soon as ...all this... is over."

"So

must I," he said simply…

…

“I could not help remembering that moment with the sun on his face

and his shining hair and the red‑leathered pocket volume open on his

lap, when months later they told me that the BRAMBLE had been

swallowed up in the black winter's night, with all hands, and then

it came to me how I should have quoted instead lines that he would

have recognised at once.

"Life to be sure is nothing much to lose,

But

young men think it is and we were young."

But in another way I am glad I didn't, for he was so splendidly

certain that everything was going to be all right, and his optimism

was a crown…

…."Do you think we shall have a flap tonight?" I asked.

"With bombing, do you mean?"

"Yes, any sort of flap."

"I

hope not for the sake of the wounded. Personally, I've got a hunch

it's going to pass off like a picnic

His

hunch was right; everything went off to plan, with one tiny

exception. At the hour of the rendezvous, the Tuscaloosa stood in

to Kola, and all night long the transferring went on and I thought:

one of those stretcher cases is Jimmy Campbell But everything was

dim and faint and muffled in the darkness. The still night: the

mountains, guarding the inlet: the faint silhouettes of the ships:

the flashing of the code signals: the passengers and the crew,

intermingled, so many shapes, taut padlocked, waiting for the final

moment. As usual, I was astonished by the precision with which the

operation was carried out: not a voice raised, not a single mishap

within the range of one's vision. (Such manoeuvres always look so

easy on paper.) The minesweepers had to come alongside the

destroyers, who, in their turn, had to slide under the bows of the

cruiser. Yet the distances were judged with the correctness of a

daylight exercise. But before daylight came, we must be gone. Hadn't

the Gossamer been sunk here only two months before? I was

glad enough when it looked like being my turn to pass over the

gangway' a human parcel being sent by Passenger Goods, one step

farther on my way.

BRAMBLE's

No.

1, Lt‑Commander Benson, came up, peering over the side. He

had been superbly efficient the whole night, and I was not surprised

to hear soon afterwards that he had been given his Brass Hat, one of

the few R.N.V.R. officers to achieve such a distinction.

"What's her name?" I asked, in a stage whisper that was quite

unnecessary, but by this time one was completely caught up in the

smuggling atmosphere.

"I'm not sure. She's American."

"American? Good God, they won't want me on board."

"Well we can't chase our own destroyers round the inlet let. There

isn't time. Didn't you see her Captain come over the side? He's down

with M.S.1 now. American ships are dry you know, and M.S.1 is giving

him a drink. I reminded him that a few tins of American peaches

wouldn't come amiss. Trust M.S.1 to put it over, if he can.‑“

Indeed, I did trust M.S.1. You couldn't help doing so. All the same,

I waited in a mounting sweat of anxiety. Should l burst in on them

and produce as a trump card the fact that I had an American

grandmother from Boston, Massachusetts? Should I tell the story of

how an English sea‑captain, sworn to celibacy, sailed across the

Atlantic and brought home with him a bride on his next voyage? I

wouldn't care if I never saw another Californian peach as long as I

live (I, too, swore to myself), if only ...

I

need not have made any such rash promise. Indeed, I got the peaches,

too. And so did the BRAMBLE, who passed some of the windfall,

I believe, on to the Pozy so that quite a few of the people in this

book had cause to be grateful to Commander Mitchell of the U.S.

Destroyer Rodman.

……….And I was left, too, with the scrap of paper M.S.1 had given me,

as a memento of so many things…. This was on the piece of paper.

“We

have in the Navy a unique expression. We talk about a ship being in

good order. It means discipline of the right sort, it means giving

of service which means more from the heart than the head, it means

happiness, it means integrity, it means modesty, it means courage

and selflessness.”

Extracts from ‘PQ17’

by Godfrey Winn who travelled to North Russia aboard HMS Pozarica

|

|

13.9.42 |

Britomart,

Halcyon, Hazard and Salamander joined QP14 from Archangel as local

eastern escort. The ocean escort included BRAMBLE, Seagull (until

26/9) and Leda (sunk on 20/9). The weather was poor during the convoy,

which finally reached Loch Ewe on 26/9 having lost 4 merchantmen and

two escorts. |

|

|

Report of Commanding

Officer HMS BRAMBLE Senior Officer of the Close Escort

(extracts)

The wind moderated in

the afternoon and with the assistance of Russian tugs the convoy

assembled successfully and weighed and proceeded at 1600 on 13th

September. Passage through the White Sea was without incident and in

fine weather. |

|

15.9.42 |

The first incident of note was at

0730 on 15th September when a Ju 88 commenced shadowing the convoy.

The convoy at this time was being escorted by two Russian fighters and

it was hoped that they would shoot down, or any way drive off this

shadower. They appeared, however, not to see her, in spite of crossing

and re-crossing at what looked like very close range to each other.

Every endeavour was made to call the attention of these fighters to

this shadower by V/S but without effect; eventually the British Naval

Liaison Officer in the Russian destroyer Uritsi reported that they

were unable to communicate with their fighters. HMS Middleton then

fired one round in the direction of the shadower. This, as I feared,

had exactly the opposite effect to that intended, and the Russian

fighters disappeared home, probably complaining that they had been

fired at.

Report

of Commanding Officer HMS BRAMBLE

|

|

16.9.42 |

During the following day the convoy was

constantly shadowed in daylight hours.The convoy made good speed and

with the prevailing current I realised that we were ahead of the

estimated position signalled by the SBNO, North Russia. On the other

hand we were not ahead of schedule based on the C in C Home Fleet's

message of 12th September.

During the afternoon of the 16th

September the weather started to deteriorate and the visibility to

decrease and I realised that these factors combined with the errors in

position would make contact difficult unless I reported the position

of QP14. Not wishing to break wireless silence I delayed making my

signal by R/T until I felt certain that the two forces were close

enough for reception to be certain. The signal reporting my position

and speed was made at 1515 on the 16th September. The weather

continued to deteriorate during the night and the convoy got a little

scattered. I ordered HMS Seagull to return along the track of the

convoy and round up SS Winston Salem and Silver Sword. SS Troubadour

had been a very early straggler and the Commodore had decided not to

wait for her.

Report of Commanding

Officer HMS BRAMBLE

|

|

16.9.42 |

It

is snowing hard this morning. We have been spotted by a Dornier and

unless the weather favours us, I guess we will all be standing by.

Source:

Diary of Jack Bowman who served on La Malouine, another of QP14's

escorts |

|

17.9.42 |

The Rear

Admiral (D) Home Fleet was sighted at 0517 17th September and after

the other destroyers had joined an A/S screen was formed in which HMS

BRAMBLE took one of the positions on the port bow of the convoy.

Report of Commanding

Officer HMS BRAMBLE

|

|

18.9.42 |

The decks are covered with ice and snow, and it is blowing a gale.

We took on oil from one of the tankers, this was done while under

way. Some of the seamen were brought in with their jaws frozen up.

It is icy-cold in the engine room. I have been so long without a

good meal I don't think I shall be able to eat one now. We passed

the island of Good Hope tonight.

Source:

Diary of Jack Bowman who served on La Malouine |

|

19.9.42 |

We are

running alongside Spitzbergen today. It is all covered in snow and

ice. I am glad that I live in the U.K. We are being shadowed by German aircraft all the time.

Source:

Diary of Jack Bowman who served on La Malouine |

|

20.9.42 |

The weather during

the passage of the convoy was poor. At 0530 on the morning of the 20th,

U435 (Strelow) torpedoed Leda which was at the rear of the convoy.

Later that day another escort (HMS Somali) and a merchantman were

torpedoed. |

|

21.9.42 |

BRAMBLE picked up

a U boat on her Asdic but was frustrated by the release of a

‘Pillenwerfer’ – compressed gas – by the submarine. |

|

22.9.42 |

0530 Three

merchant ships were sunk by U435, including one with the previously

rescued Commodore Dowding who was picked up by Seagull where he

remained. |

|

24.9.42 |

A gale hit the

convoy but it abated on the 25th leaving the convoy

struggling southwards in a heavy swell. |

|

26.9.42 |

BRAMBLE and

Seagull left the convoy for Scapa. |

|

26.9.42

|

Scapa

|

3.10.42

|

27/9

BRAMBLE has collision damage Port side of foc'sle stove in from stem

to 30ft aft in collision |

|

|

'BRAMBLE came back to England Oct/Nov 1942 and to add one injustice

upon another, as she was approaching Scapa Flow she was hit by one of

our own destroyers who gouged a large section of the side of the ship

out, fortunately above the water line. No casualties.

This necessitated a court marshal sitting in Scapa Flow at which

Captain Crombie attended. He was completely exonerated of blame but

the captain of the other ship was found guilty of 'dangerous driving'!

BRAMBLE went into dry dock and extensive repairs and modernisation

took place like the fitting of the latest anti submarine devices and

extra guns to combat the air attacks.

'

Source:Rodbourn

http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/ww2/U597628 |

|

4.10.42

|

Humber

|

5.11.42

|

6/10

BRAMBLE taken in hand by Humber Shipwright Co, Hull

for

damage repairs and refit. Provisional date of completion 16/11.

14/10 Date of completion now 30/11 |

|

7.11.42

|

Scapa

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

…..Commander Wynne-Edwards (of the recently sunk HMS Leda) turned up

too, not looking in the least like a survivor who, a fortnight before,

had been clinging to a Carley float, but in a brand new uniform, and

with a brand new ship awaiting his command, to take over from a Yankee

shipyard, and yes, he had equally positive news of Aarl. “He’s got

promotion. He is to be the Pilot of the BRAMBLE, when she goes back to

Russia. He’s tickled to death,” his late Captain added.

“And

what about your No.1 in the Leda?” I asked. “I suppose you’ve heard

he’s made it with his girl in Aberdeen. He sent me a piece of the

cake. I meant to keep it for today, but I ate it!”

“No.1

in the Leda? Oh, he’s going back on the same run too as No.1 in the

BRAMBLE. That’s a step up for him, also. Benson is getting his brass

hat, you know. While M.S.1 is due to go to the Admiralty, as Director

of Minesweeping.”

Extracts from ‘PQ17’

by Godfrey Winn who travelled to North Russia aboard HMS Pozarica

|

|

|

|

16.11.42 |

Cdr H J

RUST - took command 16 Nov 1942 |

|

25.11.42 |

Captain Crombie and some of the crew visited Aireborough

groups and schools.

The town had raised £140,000 to buy the ship in 1939. |

|

21.12.42

|

Aultbea

|

22.12.42 |

|

|

22.12.42 |

BRAMBLE (Commander H T Rust, Senior Officer of close escort) was part

of the escort for JW51B from Loch Ewe to North Russia, leaving 22/12. The convoy met bad weather |

|

|

|

|

The orders were from

Admiral Tovey and said:

‘Convoy

JW 51B 16 ships. Sail from Loch Ewe 22 December. Speed of advance 7 ½

knots routed as follows…Escort Loch Ewe, HMS BRAMBLE (S.O. M/S

Flotilla), Blankney, Ledbury, Chiddingfold, Rhodedendron, Honeysuckle,

Northern Gem and Vizalma’.

There

was, as usual, the fun of picking code names for the individual ships

and groups for use on the voice radio. Thus, BRAMBLE became

‘Prickles’…

At Loch Ewe the convoy and

escort conferences on Tuesday, 22nd December were held in a wooden

hut, and a strong wind was blowing as if to remind all present that is

was a bleak Scottish winter. In fact it was the precursor of a vicious

gale…Sherbrooke held an escort conference giving his orders to the

escorts – under Cdr. H T Rust, DSO, in the minesweeper BRAMBLE – which

would take the convoy up to position ‘C’, off Iceland, where

Sherbrooke and his destroyers would meet it and take over. Rust was an

old friend – the two men had been in the same term at Dartmouth and

each had a complete trust in each other.

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope |

|

|

|

24.12.42 |

Convoy located by

German air reconnaissance and shadowed by U534. Clearing weather and a

bright yellow moon showed up the ships of the convoy. |

|

25.12.42 |

On Christmas day the

convoy was about 150 miles east of Seidisfiord… Admiral Tovey had

signalled earlier the day before that a westbound U-boat was nearby,

and its course must have taken it within a short distance of the

convoy…And just after the U-boat signal the Admiral had wirelessed to

Rust: Your position was probably reported by a FW aircraft at 1315.

…(In fact the aircraft did not report the convoy.)

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope |

|

25.12.42 |

Six destroyers

joined 150 miles east of Iceland, their commander relieving Rust as

senior officer. The convoy was closed up in four columns with BRAMBLE

and Hyderabad, both of which possessed good radar sets, were sent

ahead on either bow as pickets. Unaware of U534’s presence JW51B

passed Jan Mayen and was half way to Bear Island when the next

depression caught up with the convoy. Storm force north-westerly winds

drove a heavy sea upon the ships’ port beams, causing them to roll.

Curtains of rain and snow swept from horizon to horizon, cutting

visibility to nil. Ice formed on decks and upper works, and parties

were sent to clear it. Below the customary ingress of water in the

escorts slopped about the messdecks churning up a soup of odds and

ends, items of clothing and broken crockery, while the bulkheads and

deckheads streamed with condensation. The convoy was broken up by the

bad weather, Oribi, Vizmala and 5 merchant ships losing contact. One,

the Jefferson Myers, hove to in order to secure her deck cargo of

bombers which was threatening to break loose from its lashings.

As the light

improved and a slight moderation in the weather allowed the remaining

nine merchant ships to be reformed, Rust was sent to search for

stragglers using BRAMBLE’s superior radar. |

|

27.12.42 |

That

night (Sunday 27th December) the barometer started falling

slowly but with an ominous steadiness: another big depression was

rolling across the North Atlantic towards them. Then the wind got up,

first just whining in the rigging and wireless aerials. Within an hour

it was beginning to howl with high-pitched urgency, bringing fair

sized seas in its train and snow squalls which blanketed off what

little visibility there was in the darkness. It was now that station

keeping became a real nightmare… soon the wind was screaming at Force

7… spray blowing over the ships started forming ice on the decks,

rails and superstructure.

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope |

|

28-29.12.42 |

Monday the 28th passed (with no let up in the weather).

Tuesday came, and with it even worse weather, the wind backing so that

in the early hours it was round to NNW, blowing at nearly 40 knots…The

wind…was as bitter as any the convoy crews had yet encountered. It was

knocking up waves of 18 feet high and blowing the crests off in

spindrift; dense streaks of foam laced the tumbling surface of the

waves, which were 700 feet apart and travelling at around 35 knots.

Within a short while the Daldorch, leading the port inner column,

signalled that her deck cargo had carried away. She could no longer

steer the convoy course (071°) and would steer 055°

until the weather eased. This probably misled the ships on the port

wing column, because at 0200 the trawler Vizalma, whose station was

the last ship in the port wing column, discovered that she and three

other ships were separated from the rest of the convoy. All four

merchantmen were finding it impossible to keep on the convoy course

because of the heavy seas and high wind, which forced their bows off,

so they hove to, all on different courses and all drifting off in

different directions.

Then

at noon on this vile Tuesday the weather suddenly moderated and

visibility in the half-light increased to 10 miles. Quickly the

anxious escorts looked for the convoy: it hardly existed as such:

instead of fourteen ships in four orderly columns, there were only

nine merchantmen in sight scattered all over the horizon…

By

this time anything up to three inches of ice had formed on the ships.

As they were, in their sheath of ice, the escorts were no longer

fighting machines…

Captain Sherbrooke’s problem was to find the missing ships: five

merchantmen, one destroyer and a trawler… A third of the convoy was

missing. It was vitally necessary to round them up as soon as

possible, before they straggled too far. Sherbrooke therefore decided

to send a ship to search with radar…He sent BRAMBLE, one of the few

escorts fitted with an effective surface-search radar set, to look for

the missing ships., and at 1230 on 29th December she was

called up by signal lamp and told to search to the north-west. Rust,

her captain, was warned that the convoy would shortly alter to due

east, the time depending on the result of the star sight.

As

soon as the final Morse ‘R’ came from BRAMBLE, showing she had

received the signal, she turned away, her radar aerials revolving, to

begin the hunt. She was never seen again by British eyes.

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope

|

|

29.12.42 |

With JW51B 150

miles south-west of Bear Island (and well astern of her dead

reckoning) three of the merchantmen rejoined, one was travelling in

company with Vizalma, while BRAMBLE was still searching for the

Jefferson Myers.

On board the

merchantman Empire Archer a disturbance broke out among her firemen

after some had broached a consignment of rum intended for the Kola

based minesweepers. In the ensuing violence two men were knifed. This

fight occurred simultaneously with the threatened break adrift of a

railway locomotive which, among a deck cargo of eight heavy tanks, had

parted some of its lashings. The drunken firemen were suppressed by

the ship’s master and his officers. Desperate for merchant seamen,

these ne’er-do-wells had been offered a bonus of £100 when they were

recruited from Scotland’s notorious Barlinnie Gaol.

|

|

30.12.42 |

Following a report

sent by U354 that the JW51B was weakly escorted and giving its

position, Admiral Hipper, Lutzow and six German destroyers were sailed

to intercept the convoy.

U354 worked its

way round to the front of the convoy and was preparing to attack the

convoy when she was sighted by Obdurate which tried to ram it but the

U-boat crash dived and escaped.

|

|

|

Wednesday 30th December, with the convoy eight days out of

Loch Ewe, found the weather a good deal better and all ships had every

available man on deck chipping off the sheath of ice.

During the morning three of the missing merchantmen rejoined the

convoy; a fourth along with an escort trawler had overtaken the convoy

in their efforts to catch up. At 1240 the convoy was spotted by U-354.

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope

|

|

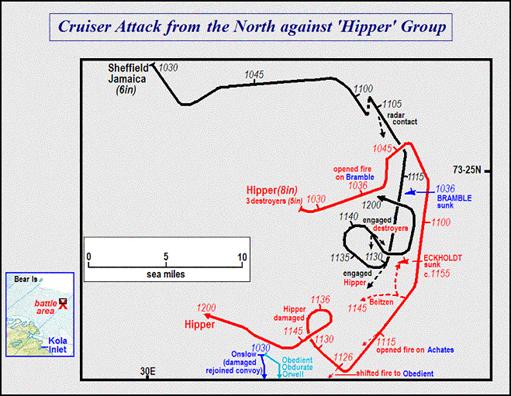

31.12.42 |

Early

on New Year ’s Eve convoy JW51B was on an easterly course, driven well

south of its planned route by the heavy gale two days earlier. Two

merchant ships, the trawler Vizalma and BRAMBLE were still missing

from the convoy. Unknown to Sherbrooke, BRAMBLE was about 15 miles

north-east of the convoy and probably steaming a similar course: while

Vizalma with Chester Valley were both about 40 miles to the north,

steering east and making 11 knots, hoping to overtake the convoy but

in ignorance of the fact it was south of them.

Thus,

as the German force (Hipper, Lutzow and six destroyers) approached

from the south-west before dawn on New Year’s Eve, the convoy was

closest to them and Force R (the cruisers Sheffield and Jamaica) was

30 miles beyond; Vizalma and the Chester Valley were even farther

north. The BRAMBLE, alone, was ahead of the convoy.

Hipper

Hipper

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope |

|

31.12.42 |

The Arctic ‘dawn’

(between 0800 and 1500 there was a ‘nautical twilight’ as the sun

never rose to more than 12° below the horizon) broke to a freezing

morning with a heavy frost and all the ships covered in a thick mantle

of ice. The wind had dropped and the sea had moderated, leaving a

heavy swell. Except where the snow squalls shut it in, visibility was

quite good, up to 10 miles to the south. About a dozen miles to the

north east BRAMBLE was still searching for the Jefferson Myers (which

was in fact miles away from BRAMBLE’s position).

Around

7:00 a.m., the convoy was seen by Hipper’s destroyers.

While the Hipper diverted herself to the North to push the convoy into

the clutches of the Lutzow, the destroyers shadowed the convoy.

|

|

31.12.42 |

At 0820 the corvette

Hyderabad made the first sighting of two destroyers due south. At this

stage it was uncertain is they were Russian or German. They were

German.

Just about this time the

minesweeper BRAMBLE transmitted a brief signal. 'One cruiser bearing

300°',

but only the Hyderabad picked it up. Apparently she assumed the signal

– the last ever received from the BRAMBLE – had been picked up by

other ships of the escort, for she did not pass it on to Kinloch, who

was unaware of it until several days later.

At about 0915 the German

destroyers Eckholdt, Beitzen and Z29 engaged Obdurate and the battle

of the Bering Sea commenced. Shortly after this, Hipper engaged Onslow.

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope

While the

convoy was sailing eastwards in the company of the Achates alone, the

other British destroyers put themselves between the convoy and the

German cruisers and destroyers. The British ships managed to avoid the

enemy fire until the Onslow was hit by four heavy shells at 10:20

a.m., suffering extensive damage. The British destroyers then vanished

in the fog.

After dealing the Onslow a

crushing blow without realising it, Admiral Kummetz ordered the Hipper

to increase to 31 knots – full speed – and steer to the ENE with his

three destroyers in company. The convoy was now more than twelve miles

away to the SSW steaming, he hoped, into the guns of the Lutzow and

the three destroyers.

Suddenly at 1036, a

destroyer or corvette – the look-outs could not be certain which in

the darkness and snow squalls – was sighted on the port side, steering

away from the Hipper. ‘I directed the Hipper to engage this ship,

which was at first taken to be a corvette or destroyer,’ wrote Kummetz,

‘because it would have meant a very unpleasant link on the lee side of

the firing in an engagement with the convoy. After finishing off the

destroyer I intended to resume action with the convoy. The destroyer

was probably an escort stationed on the flank of the convoy.’

In fact the ‘destroyer’

was the 875 tonne minesweeper BRAMBLE, commanded by Cdr H T Rust, and

manned by seven officers and 113 ratings. She had one 4 inch gun

firing a 31 pound shell against the Hipper’s eight 8 inch and twelve

4.1 inch. Immediately the Hipper was sighted, Rust must have sent off

an enemy report – received only by Hyderabad – knowing nothing could

save him. At 1043 HMS Hyderabad picked up the following message on

Fleet Wave:

Addressed ONSLOW from BRAMBLE.

One cruiser bearing 300 degrees.

T.O.O. 1039A

|

Apparently Hyderabad

assumed the signal – the last ever received from the BRAMBLE – had

been picked up by other ships of the escort, for she did not pass it

on to Kinloch, who was unaware of it until several days later.

The Hipper’s guns did not

sink BRAMBLE, even though they were firing for six minutes, and at

1046 Kummetz ordered the Freidrich Eckholdt by radio-telephone:

'Sink the destroyer in position 1500. Destroyer was fired on by Hipper'.

Kummetz then swung the Hipper round to get nearer the convoy

again.

Source: Extracts from ’73

North’, Dudley Pope

|

|

31.12.42 |

BRAMBLE

had managed to fire a single round at Hipper from her 4" gun and a few

rounds from her Oerlikons before being overwhelmed by the cruiser's

heavy weapon fire. BRAMBLE sank

at 11:58, eight officers including her captain Cdr H J Rust and 113

ratings were drowned.

In the subsequent

action, the Eckholdt herself was sunk when she mistook the Sheffield

for Hipper. Sheffield swept past at point blank range with the

full-calibre weapons depressed at an elevation never previously

attempted, firing into the enemy destroyer with ‘all guns down to

pom-poms’ and destroying her in minutes.

The outclassed

German ships retired and contact was lost at about 1400. The convoy

proceeded unmolested. |

|

2.1.43 |

During

the afternoon Harrier and Seagull joined as part of the eastern local

escort, leading the main body of the convoy into Kola where it arrived

the next day, though final berthing was delayed by dense fog.

The

Jefferson Myers finally made her way into Molotovsk, escorted by a

Russian destroyer, on 6/1. |

8.1.43 |

The Board of Enquiry reported on the presumed loss

of HMS BRAMBLE.

CLICK HERE for details

|

|

Source:

http://www.naval-history.net/Cr03-55-00BarentsSea2.htm

|

A

Memorial Service for BRAMBLE was held in Aireborough: BRAMBLE was

special to Aireborough because in one week residents raised £140,000

to buy it in Warships Week (March

14 1942 until March 21 1942) and prior to its sinking the crew members, including

Captain Harvey Crombie visited Aireborough groups and schools.

At the memorial service held in Guiseley Parish Church, the Captain

said:

"They had braved

difficulties and perils probably unparalleled in the annals of the

British Navy, and calls upon their courage and endurance were

constant, but they never failed. They would not have us think sadly at

this time, but rather that we should praise God that they had remained

steadfast to duty to the end."

|

|